Executive Summary

We all know that a seminar alone is not likely to result in significant changes in job performance, and much has been written about different techniques for ensuring that skills transfer into organizational performance improvement. However, while many have promoted specific activities to support the transfer of learning, there has been little research comparing the actual impact of these different techniques. In this study, we reviewed the literature from the past two years and found 32 research studies that compared the impact of training seminars alone to training plus one or more learning transfer activities. This research allowed us to identify 11 specific actions that have a significant impact on whether training results in measurable performance improvement. Overall, we found that if an organization implemented all of these actions, they could improve the effectiveness of their learning by over 180%. The outcome of this research is a model of Learning Transfer that is cost-effective to implement, captures the majority of transfer improvement actions, and has the maximum likelihood of improving the effectiveness of learning in your organization.

Learning Transfer: Enhancing the Impact of Learning on Performance

The fundamental purpose of learning and development is to help people develop skills which, when applied to work, enhance job and organizational performance. While this is widely acknowledged, how we measure the success of learning is not often in alignment with this idea. In fact, the most popular model for evaluating learning and development (Kirkpatrick Model) has three “levels” devoted to measuring learning outcomes and only one measuring performance outcomes.

This focus on learning outcomes, rather than performance outcomes, has also influenced how learning has been designed and delivered for most of our industry’s history. More recently, it has been widely researched (and largely accepted) that learning and development, as usually conducted, does not create performance change at an acceptable rate. In fact, most estimates suggest that only about 15–20% of the learning investments organizations make actually result in work performance changes.

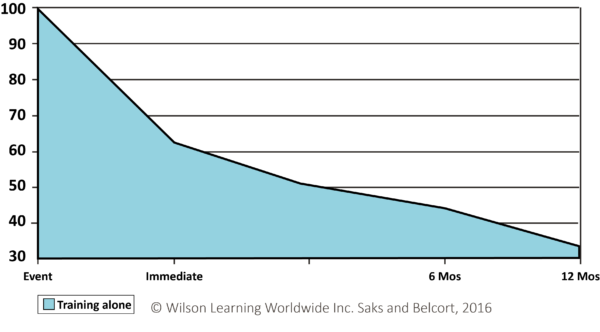

For example, the following graph (from research conducted by Saks and Belcort in 2006) shows the decline in the use of learning on the job over time. The research clearly shows that for the average training and development program, there is a steady decline in the use of new skills. It is estimated that only about 35% of the skills are still in use 12 months after the typical training event.

Over the years, a number of people have offered theoretical models for how to enhance learning so it results in greater impact on performance. This work goes under many names: extended learning, learning transfer, transfer climate, and relapse prevention, to name a few. In this article, we will use the term Learning Transfer, because in our opinion, Learning Transfer best represents the desired outcome—transfer of learning to actual job performance.

Over the years, a number of people have offered theoretical models for how to enhance learning so it results in greater impact on performance. This work goes under many names: extended learning, learning transfer, transfer climate, and relapse prevention, to name a few. In this article, we will use the term Learning Transfer, because in our opinion, Learning Transfer best represents the desired outcome—transfer of learning to actual job performance.

There are several limitations to these theoretical models. First, most of them are rather complex, containing a large number of factors. Second, they are difficult, maybe impossible, to implement in any practical setting. Finally, while some of the models have a basis in research, they all began from a theoretical perspective, rather than from a practical perspective.

Therefore, the purpose of this research was to answer two basic questions: Can we identify sufficient research that documents the impact of specific learning transfer activities on the use of skills on the job? Then, from that research, can we construct a model that captures the essential components that support learning transfer most effectively?

The Study

The first task of this study was to identify published and unpublished research that met three specific criteria:

- The research compared training alone to training plus one or more learning transfer activities.

- The research reported statistically significant differences between training alone and training plus the learning transfer activities. This had to be more than anecdotal information so we could compare across studies.

- The outcome measures reported in the results needed to be performance outcomes, not learning outcomes.

Using a variety of sources, we identified research studies that met these criteria. We reviewed each study to identify the learning transfer action used and identified how the performance difference was measured between training alone and training plus learning transfer activity. Many of the studies implemented multiple learning transfer activities. As a result, we identified 32 studies that examined 66 learning transfer activities.

Each study used its own statistical method for calculating the performance impact of the learning transfer activities (regression, ANOVA, t-test, etc.). Therefore, for each learning transfer activity, we used the available statistical data and calculated a “difference score” which represented the relative contribution of each learning transfer activity to the difference between training alone and training plus that learning transfer activity. That allowed us to compare across studies, even though they used different statistical methods. This difference score represented the percentage improvement of training plus learning transfer over training alone. For example, a difference score of 20 indicated that the learning transfer activity improved the performance of the participants 20% over training alone.

Finally, to create a model that is less complex and easier to implement than the previous theory-driven models, we grouped similar transfer actions into common transfer activity categories. This led us to the Learning Transfer Model described below.

Findings

In summary, there are three broad conclusions that can be drawn from this research.

- This study provides convincing evidence that learning transfer activities have a meaningful impact on improving the performance results achieved from training alone. Taken together, the research suggests that the impact of learning can be enhanced by as much as 186% when all of the learning transfer methods are utilized.

- While learning transfer has a tremendous impact on performance, any one method may have a relatively modest impact. We found that taken alone, most learning transfer activities will improve performance about 20% over training alone. While significant, this is much below what others claim will happen.

- Finally, there is tremendous variability from study to study on the impact of learning transfer activities. While all of the studies tended to show significant and positive performance impact, the specific percent improvement varied widely. This clearly shows the need for further research in this area.

Learning Transfer Model

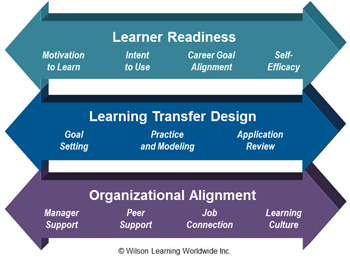

As described above, we found that the learning transfer activities researched in these 32 studies can be grouped into three primary categories.

As described above, we found that the learning transfer activities researched in these 32 studies can be grouped into three primary categories.

- Learner Readiness Activities: These activities focus on ensuring that the learner is prepared for the core learning event. Activities that address motivation, learner goals, self-efficacy, and testing of prerequisite skills are included in this category.

- Learning Transfer Design Activities: These are activities embedded in the instructional design that are intended to support learning transfer. Practice activities, role modeling, setting learning goals, and application review and support are examples.

- Organizational Alignment Activities: These activities focus on ensuring that the organization supports the use of the skills. Activities here include manager coaching, peer support, connecting learning to the job, and creating a learning culture.

Within each primary category, three to four specific learning transfer activities have been subject to research and have been shown to have an impact on performance.

Impact of Learning Transfer on Performance Outcomes

The table below shows the percentage impact (difference scores) for the different categories of learning transfer activities. For each activity, the table shows the number of studies that included that activity, average difference score, and the range of difference scores.